Legends are steamy things. We are talking about Arthur, former and future king of Great Britain, who united The Empire against the Saxon invaders. Where historical facts are elusive, The literary imagination has imagined Arthur’s idyllic Camelot Court, its chambers full of knights, wizards and witches, its halls full of chivalry, romance and betrayal. Exploring the Legend of Arthur, Pendragon mixes interactive fiction and tactical action in a short and Roguelike structure to tell countless stories. As a study of how myths are formed from countless half-truths, it is effective. But as a narrative journey, it feels light, its most admirable efforts are undermined by repetition and a troubled relationship with the fight.

In this particular interpretation of the Arthurian legend, the story always begins in 673 AD, about a week before Arthur reached the castle of Camlann to confront his son Mordred, whose challenge to the throne triggered a civil war. Every time you launch a new game, you play as one of the states of Arthur’s Court – his ex-wife Guinevere, his possible lover Sir Lancelot, The enigmatic Merlin, to name just three of the most famous characters -and you rush across Britain to help the king in the decisive showdown. Along the way, you will meet characters who can convince you to go up with your banner, others to be put to the sword and an alarming number of wolves, snakes, giant spiders and rats to action or flee. Although rest and rations help the wounded recover, everyone in your party – even your starting character – can die permanently, and the journey is over when everyone falls in battle. A full run usually only takes 20 to 30 minutes, depending on how fast you find Camlann.

The rapid turnaround of a race highlights the momentum of Pendragon’s narrative. As you embark on a new journey, you will quickly find yourself exploring a reconfigured map, discovering new places and historical events, and gathering alternative perspectives on the fundamental myths of the country. And the game does a remarkable job of connecting the many distinct narrative threads that you can follow throughout a race. In a race, I started as Morgana Le Fay before meeting and recruiting Guinevere. Morgana was then wounded in actionwhile Guinevere fled, leaving me to play the role of the latter. By the time I reached Camlann, Guinevere had also perished, and so I faced the Knights of Mordred, with only Arthur’s brother, Sir Kay, and a heavily supply peasant in tow. What is impressive is that the dialogue does not lack rhythm; the conversations feel coherent and respond to every choice and chaos that has occurred along the way.

Of course, there are limits. When I was on my fifth or sixth trip, I realized that some scenarios were repeating themselves. For example, when I arrive in the burnt-out village, I could say that I could recruit this blacksmith here. But while some of the individual components become trustworthy over time, the unpredictable order in which they occur and the different choices they can make make each trip unique as a whole.

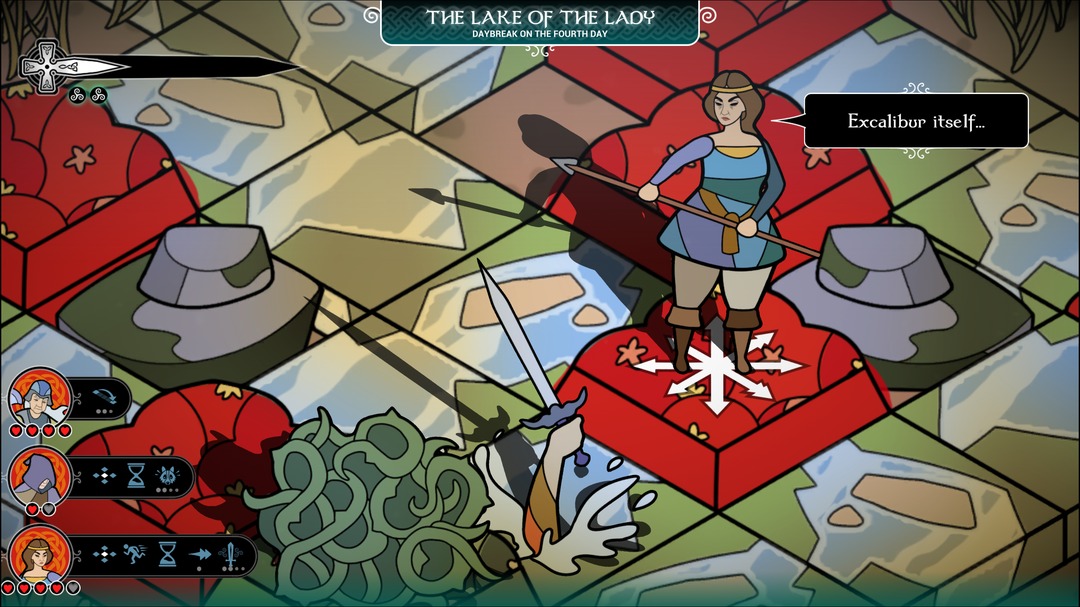

Meetings, whether friendly or hostile, take place on a small isometric grid, often no more than half a dozen square tiles. The characters alternate between postures that inform their movement and the available actions; with The Weapon drawn, they can attack but only move linearly, while diagonal movements are only possible with The Wrapped Weapon. As a action machine, it is relatively simple, but capable of taking on interesting challenge s through a few additional complexities. Outwitting a group of enemies – baiting them with one character while a second uses a special ability from the flank, or changing their posture at the crucial moment to prevent an attack – seems well deserved, because every action carries a real danger. The compacted nature of a barrel means that there is no sanding and little loading.

You don’t always action either. In fact, many experiences end without the steel being pulled. The characters discuss as they move back and forth down the line, weighing the situation. This verbal action, associated with the sliding movements where each participant adjusts his posture and his behavior, resembles a kind of formal dance routine, each step being accompanied by a witty counter-speech.

On the other hand, such experiences emphasize that Pendragon is weakest when he is not telling a story. The straight-line action dampens the momentum of the journey. I had a race where Merlin and his companion fled from a pack of wolves to meet another that they could not defeat. After escaping, they came across another pack and, with the ability to escape now suppressed, were killed in a premature and overwhelming end to their quest.